Researchers catch atoms standing still inside molten metal

- Date:

- December 11, 2025

- Source:

- University of Nottingham

- Summary:

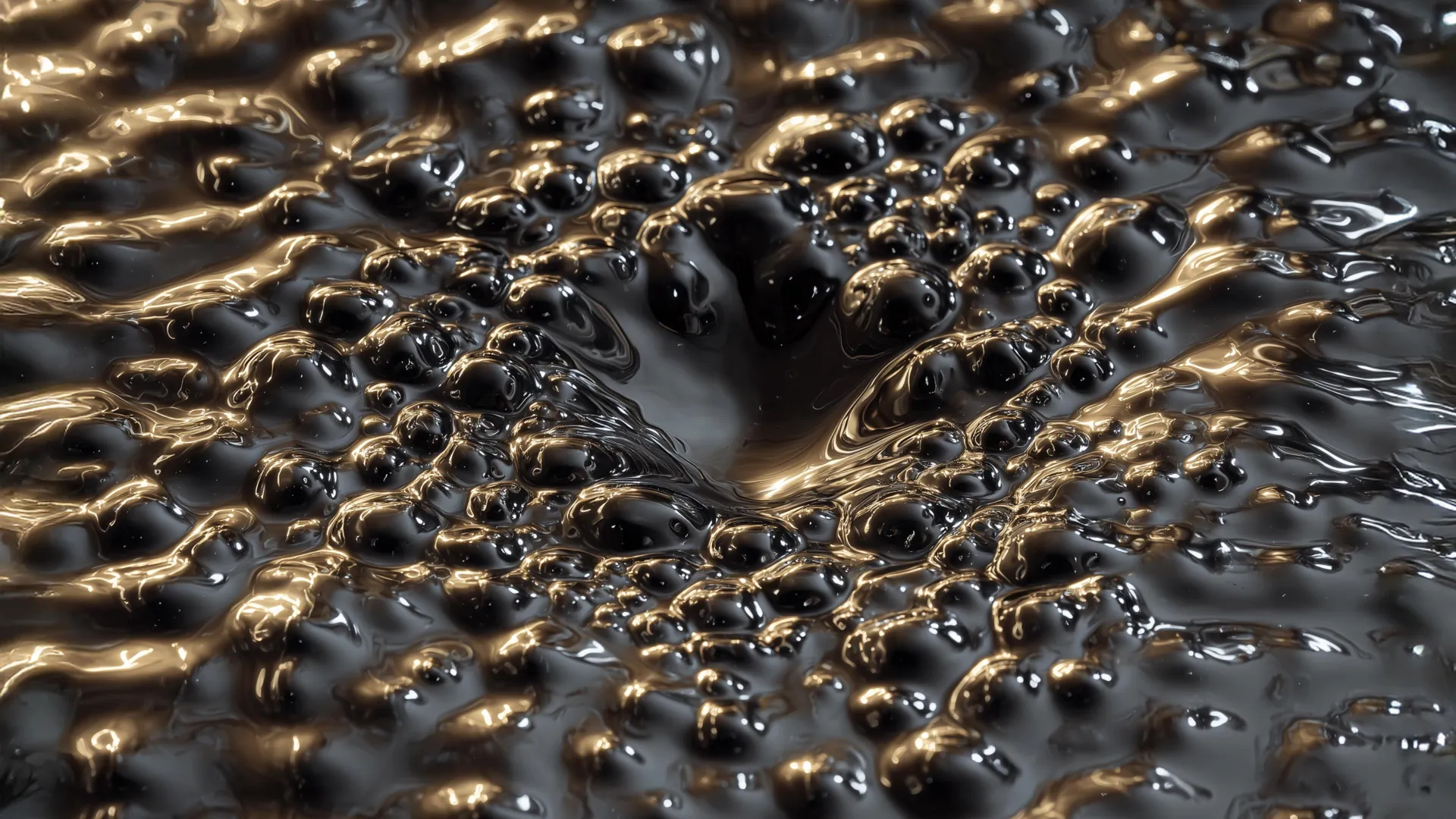

- Scientists have uncovered that some atoms in liquids don't move at all—even at extreme temperatures—and these anchored atoms dramatically alter the way materials freeze. Using advanced electron microscopy, researchers watched molten metal droplets solidify and found that stationary atoms can trap liquids in tiny “atomic corrals,” keeping them fluid far below their normal freezing point and giving rise to a strange hybrid state of matter.

- Share:

Researchers have found that, inside a liquid, not every atom is moving. Some atoms stay fixed in place even when the temperature is very high. These motionless atoms have a major effect on how a liquid turns into a solid, including the creation of an unusual state of matter known as a corralled supercooled liquid.

The way materials solidify is crucial in many natural processes, such as mineralization, the formation of ice, and the folding of protein fibrils. Solidification is also central to many technologies, from pharmaceuticals to metal-based industries, including aviation, construction, and electronics.

Imaging Molten Metal at the Atomic Scale

To explore how solids form, scientists from the University of Nottingham and the University of Ulm in Germany used transmission electron microscopy to watch molten metal nano-droplets as they solidified. Their findings were published on December 9 in the journal ACS Nano.

Professor Andrei Khlobystov, who led the team, said, "When we consider matter, we typically think of three states: gas, liquid, and solid. While the behavior of atoms in gases and solids is easier to understand and describe, liquids remain more mysterious."

Complex Motion Inside Liquids

In liquids, atoms move in a complicated, crowded way, similar to people jostling through a busy street. They zip past one another at high speed while still interacting. This motion is especially difficult to study during the key moment when a liquid begins to solidify, a stage that sets the material's structure and many of its functional properties.

Graphene "Hob" Experiments and the SALVE Instrument

Dr. Christopher Leist, who performed transmission electron microscopy experiments at Ulm using the unique low-voltage SALVE instrument, said, "We began by melting metal nanoparticles, such as platinum, gold, and palladium, deposited on an atomically thin support -- graphene. We used graphene as a sort of hob for this process to heat the particles, and as they melted, their atoms began to move rapidly, as expected. However, to our surprise, we found that some atoms remained stationary."

Further analysis showed that these stationary atoms are strongly attached to the supporting material at specific locations called point defects, and this strong bonding persists even at very high temperatures. By concentrating the electron beam on selected areas, the team could create more defects and therefore adjust how many atoms stayed pinned in place within the liquid.

Wave-Particle Duality and a New Phase of Matter

Professor Ute Kaiser, who established the SALVE center at Ulm University, said, "Our experiments have surprised us as we directly observe the wave-particle duality of electrons in the electron beam. We visualize the material using electrons as waves. At the same time, electrons behave like particles, delivering discrete bursts of momentum that can either move or, surprisingly, even fix atoms at the edge of a liquid metal. This remarkable observation has allowed us to discover a new phase of matter."

The same research team has previously produced films of chemical reactions involving single molecules, including the first direct recording of a chemical bond breaking and reforming in real time. Their approach makes it possible to watch chemistry unfold at the level of individual atoms.

Atomic Corrals and Disrupted Crystal Growth

In the new study, the scientists discovered that stationary atoms play a powerful role in directing how a liquid turns solid. When only a few atoms are pinned, a crystal can grow from the liquid and continue to expand until the entire nanoparticle becomes solid. In contrast, when many atoms are held in place, they interfere with this process and block the formation of any crystal at all.

Professor Andrei Khlobystov from the University of Nottingham said "The effect is particularly striking when stationary atoms create a ring that surrounds the liquid. Once the liquid is trapped in this atomic corral, it can remain in a liquid state even at temperatures significantly below its freezing point, which for platinum can be as low as 350 degrees Celsius -- that is more than 1,000 degrees below what is typically expected."

Corralled Supercooled Liquid and Unstable Amorphous Metal

If the temperature is lowered enough, the corralled liquid eventually turns solid, but not into a regular crystal. Instead, it becomes an amorphous solid, a form of metal without the ordered structure of a crystal. This amorphous metal is highly unstable and exists only as long as the stationary atoms continue to confine it. Once that confinement breaks down, the built-up tension is released and the metal rearranges into its usual crystalline form.

Hybrid Metal State and Catalysis

Dr. Jesum Alves Fernandes, expert in catalysis at the University of Nottingham, said, "The discovery of a new hybrid state of metal is significant. Since platinum on carbon is one of the most widely used catalysts globally, finding a confined liquid state with non-classical phase behavior could change our understanding of how catalysts work. This advancement may lead to the design of self-cleaning catalysts with improved activity and longevity."

Toward New Forms of Matter and Cleaner Technologies

Up to now, nanoscale corralling has only been achieved for photons and electrons; this study is the first demonstration that atoms themselves can be corralled in a similar way. Professor Andrei Khlobystov said, "Our achievement may herald a new form of matter combining characteristics of solids and liquids in the same material."

The researchers suggest that by carefully arranging the positions of pinned atoms on a surface, they may be able to build larger and more intricate atomic corrals. Such control over rare metals could lead to more efficient use of these materials in clean technologies, including energy conversion and energy storage.

This work is funded by the EPSRC Program Grant 'Metal atoms on surfaces and interfaces (MASI) for sustainable future.'

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Nottingham. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Christopher Leist, Sadegh Ghaderzadeh, Emerson C. Kohlrausch, Johannes Biskupek, Luke T. Norman, Ilya Popov, Jesum Alves Fernandes, Ute Kaiser, Elena Besley, Andrei N. Khlobystov. Stationary Atoms in Liquid Metals and Their Role in Solidification Mechanisms. ACS Nano, 2025; DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.5c08201

Cite This Page: