Spacecraft captures the "magnetic avalanche" that triggers giant solar explosions

New observations reveal how solar flares really ignite—and why they can be so powerful.

- Date:

- January 21, 2026

- Source:

- European Space Agency

- Summary:

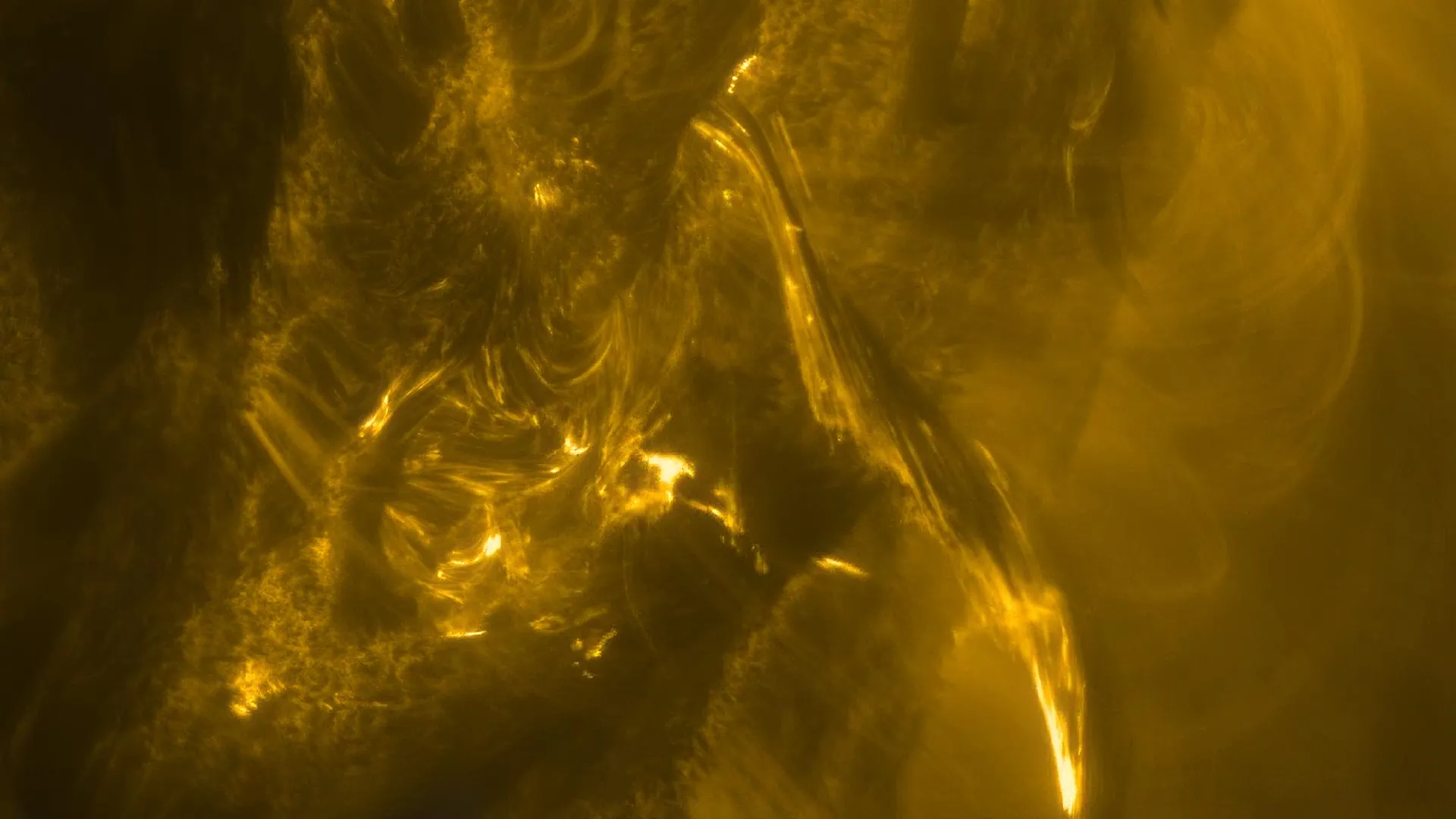

- Solar Orbiter has captured the clearest evidence yet that a solar flare grows through a cascading “magnetic avalanche.” Small, weak magnetic disturbances rapidly multiplied, triggering stronger and stronger explosions that accelerated particles to extreme speeds. The process produced streams of glowing plasma blobs that rained through the Sun’s atmosphere long after the flare itself.

- Share:

Much like a snow avalanche that starts with a small shift before cascading downhill, new observations show that solar flares begin with subtle magnetic disturbances that rapidly intensify. Scientists using the European Space Agency (ESA) led Solar Orbiter spacecraft discovered that these early changes can quickly grow into violent eruptions, producing a dramatic cascade of glowing plasma blobs that fall through the Sun's atmosphere long after the main flare has peaked.

This insight comes from one of the most detailed views ever captured of a large solar flare. The event was recorded during Solar Orbiter's close pass by the Sun on 30 September 2024 and is described in a study published today (January 21) in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

What Triggers a Solar Flare

Solar flares are among the most powerful explosions in the solar system. They occur when enormous amounts of energy stored in twisted magnetic fields are suddenly released through a process known as magnetic reconnection. During reconnection, magnetic field lines pointing in opposite directions break apart and reconnect in a new configuration. This rapid rearrangement can heat plasma to millions of degrees and hurl energized particles away from the site, creating a solar flare.

The strongest flares can set off a chain reaction that reaches Earth, triggering geomagnetic storms and sometimes disrupting radio communications. Because of these potential impacts, scientists are eager to understand exactly how flares begin and evolve.

For years, the precise mechanism behind the Sun's ability to release such vast energy in minutes remained unclear. Now, a rare combination of observations from four Solar Orbiter instruments working together has provided the most complete picture yet of how a flare unfolds from its earliest moments.

A Rare Look at the Birth of a Solar Flare

Solar Orbiter's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) captured remarkably detailed images of the Sun's outer atmosphere, known as the corona, resolving features only a few hundred kilometers across and recording changes every two seconds. At the same time, three additional instruments, SPICE, STIX and PHI, studied different layers of the Sun, from the hot corona down to the visible surface, or photosphere.

Together, these observations allowed scientists to track the buildup to the flare over roughly 40 minutes, an opportunity that rarely occurs due to limited observing windows and onboard data constraints.

"We were really very lucky to witness the precursor events of this large flare in such beautiful detail," says Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany, and lead author of the paper. "Such detailed high-cadence observations of a flare are not possible all the time because of the limited observational windows and because data like these take up so much memory space on the spacecraft's onboard computer. We really were in the right place at the right time to catch the fine details of this flare."

Magnetic Avalanche in Action

When EUI began observing the region at 23:06 Universal Time (UT), about 40 minutes before the flare reached its peak, it revealed a dark, arch shaped filament made of twisted magnetic fields and plasma. This structure was connected to a cross shaped pattern of magnetic field lines that gradually grew brighter. (See video link below article.)

Close up views showed that new magnetic strands appeared in nearly every image frame, roughly every two seconds or less. Each strand remained confined by magnetic forces and gradually twisted, resembling tightly wound ropes.

As more strands formed and twisted, the region became unstable. Like an avalanche gaining momentum, the magnetic structures began breaking and reconnecting in rapid succession. This triggered a spreading chain of disruptions, each one stronger than the last, visible as sudden bursts of brightness.

At 23:29 UT, a particularly intense brightening occurred. Soon after, the dark filament detached on one side and shot outward, unrolling violently as it moved. Bright flashes of reconnection appeared along its length in extraordinary detail as the main flare erupted around 23:47 UT.

"These minutes before the flare are extremely important and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began," says Pradeep. "We were surprised by how the large flare is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that spread rapidly in space and time."

Solar Flares as Cascading Chain Reactions

Scientists have long suggested that avalanches could explain the collective behavior of countless small flares on the Sun and other stars. Until now, it was unclear whether the same idea applied to a single, large flare.

These new results show that a major flare does not have to be one unified explosion. Instead, it can emerge from many smaller reconnection events that interact and build on one another, forming a powerful cascade.

Raining Plasma Blobs

Using combined measurements from the SPICE and STIX instruments, the research team was able to study how this rapid sequence of reconnection events deposits energy into the uppermost layers of the Sun's atmosphere with unprecedented detail.

High energy X rays played a key role in this analysis, as they reveal where accelerated particles release their energy. Because such particles can escape into space and pose risks to satellites, astronauts, and even technologies on Earth, understanding their behavior is essential for predicting space weather.

During the 30 September flare, ultraviolet and X ray emissions were already slowly increasing when SPICE and STIX began their observations. As the flare intensified, X ray output surged dramatically, accelerating particles to speeds of 40 to 50 percent of the speed of light, or roughly 431 to 540 million km/h. The data also showed energy moving directly from magnetic fields into the surrounding plasma during reconnection.

"We saw ribbon-like features moving extremely quickly down through the Sun's atmosphere, even before the main episode of the flare," says Pradeep. "These streams of 'raining plasma blobs' are signatures of energy deposition, which get stronger and stronger as the flare progresses. Even after the flare subsides, the rain continues for some time. It's the first time we see this at this level of spatial and temporal detail in the solar corona.

Cooling After the Eruption

After the most intense phase of the flare passed, EUI images showed the original cross shaped magnetic structure relaxing. At the same time, STIX and SPICE recorded cooling plasma and a drop in particle emissions toward normal levels. PHI observed the effects of the flare on the Sun's visible surface, completing a three dimensional view of the entire event.

"We didn't expect that the avalanche process could lead to such high energy particles," says Pradeep. "We still have a lot to explore in this process, but that would need even higher resolution X-ray imagery from future missions to really disentangle."

A New Understanding of Solar Explosions

"This is one of the most exciting results from Solar Orbiter so far," says Miho Janvier, ESA's Solar Orbiter co-Project Scientist. "Solar Orbiter's observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasise the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work. An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars."

"These exciting observations, captured in incredible detail and almost moment by moment, allowed us to see how a sequence of small events cascaded into giant bursts of energy," says David Pontin of the University of Newcastle, Australia, who co-authored the paper.

He adds: "By comparing the EUI observations with magnetic-field observations, we were able to disentangle the chain of events that led to the flare. What we observed challenges existing theories for flare energy release and, together with further observations, will allow us to refine those theories to improve our understanding."

About the Solar Orbiter Mission

Solar Orbiter is a joint mission between ESA and NASA and is operated by ESA. The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) is led by the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB). The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) is led by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), Germany. The Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) is a European led instrument managed by the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS) in Paris, France. The STIX X ray Spectrometer and Telescope is led by FHNW, Windisch, Switzerland.

Story Source:

Materials provided by European Space Agency. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- L. P. Chitta, D. I. Pontin, E. R. Priest, D. Berghmans, E. Kraaikamp, L. Rodriguez, C. Verbeeck, A. N. Zhukov, S. Krucker, R. Aznar Cuadrado, D. Calchetti, J. Hirzberger, H. Peter, U. Schühle, S. K. Solanki, L. Teriaca, A. S. Giunta, F. Auchère, L. Harra, D. Müller. A magnetic avalanche as the central engine powering a solar flare. Astronomy, 2026; 705: A113 DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202557253

Cite This Page: