Parkinson’s breakthrough changes what we know about dopamine

Dopamine isn’t the brain’s throttle—it’s the oil that keeps movement running, and that insight could change Parkinson’s care.

- Date:

- December 22, 2025

- Source:

- McGill University

- Summary:

- A new study shows dopamine isn’t the brain’s movement “gas pedal” after all. Instead of setting speed or strength, it quietly enables movement in the background, much like oil in an engine. When scientists manipulated dopamine during movement, nothing changed—but restoring baseline dopamine levels made a big difference. The finding could reshape how Parkinson’s disease is treated.

- Share:

A new study led by researchers at McGill University is calling into question a long-standing idea about how dopamine influences movement. The findings suggest a shift in how scientists understand Parkinson's disease and how its treatments work.

The research, published in Nature Neuroscience, shows that dopamine does not directly control how fast or how forcefully a person moves, as many experts previously believed. Instead, dopamine appears to provide the basic conditions that allow movement to happen in the first place.

"Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine's role in movement," said senior author Nicolas Tritsch, Assistant Professor in McGill's Department of Psychiatry and researcher at the Douglas Research Centre. "Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be enough to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson's treatment."

What Dopamine Does in Parkinson's Disease

Dopamine plays a key role in motor vigor, which refers to the ability to move with speed and strength. In people with Parkinson's disease, the brain cells that produce dopamine gradually break down. This loss leads to hallmark symptoms such as slow movement, tremors, and problems with balance.

Levodopa, the most common treatment for Parkinson's, helps restore movement by increasing dopamine levels in the brain. However, scientists have not fully understood why the drug is so effective. In recent years, improved brain-monitoring tools detected brief spikes of dopamine during movement. These rapid bursts led many researchers to think dopamine directly controlled movement intensity.

The new findings challenge that assumption.

Dopamine Acts as Support, Not a Speed Controller

The study suggests dopamine does not act as a moment-by-moment controller of movement. Instead, it serves a more fundamental role.

"Rather than acting as a throttle that sets movement speed, dopamine appears to function more like engine oil. It's essential for the system to run, but not the signal that determines how fast each action is executed," said Tritsch.

Tracking Dopamine in Real Time

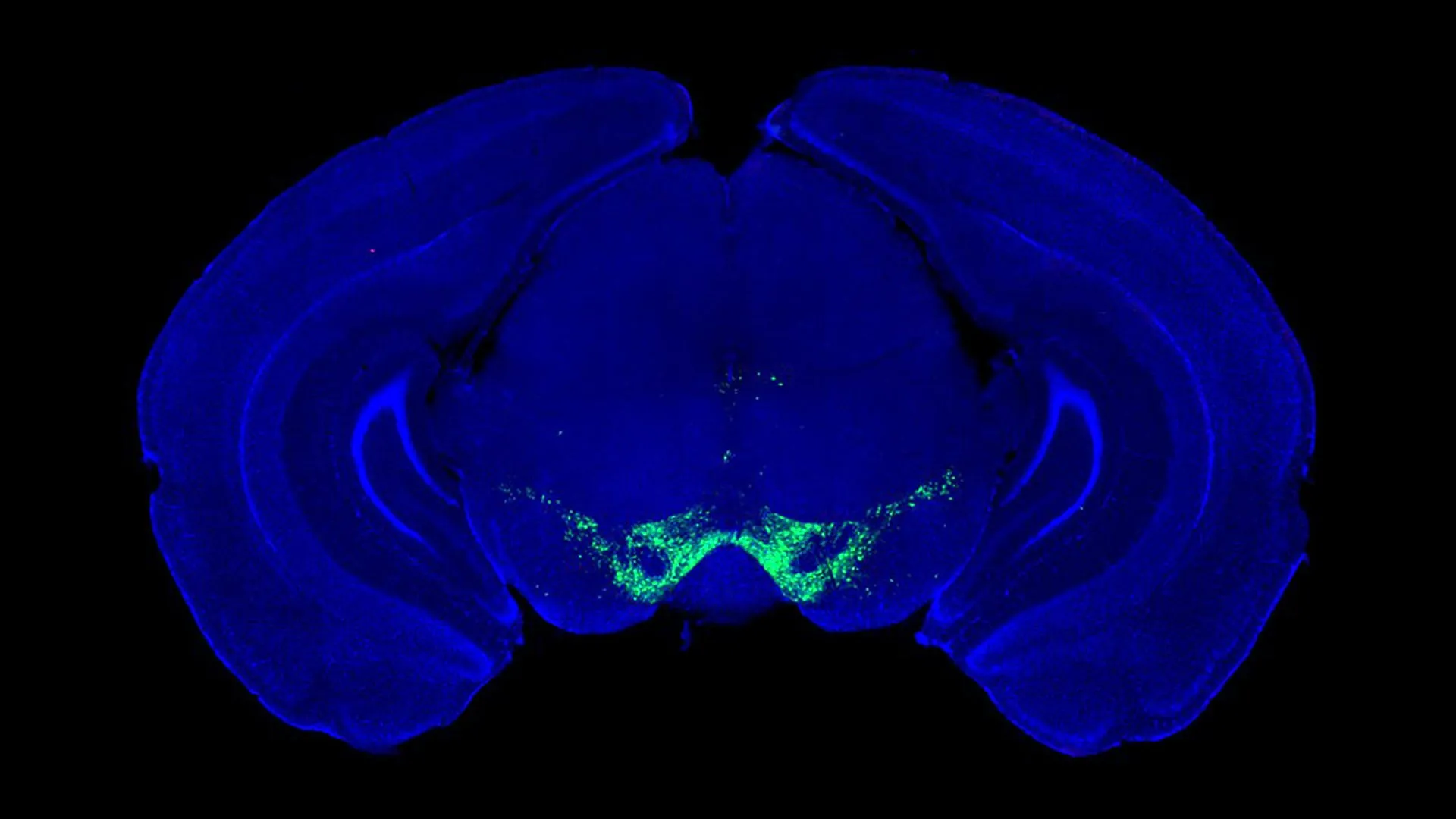

To test this idea, the researchers monitored brain activity in mice while the animals pressed a weighted lever. Using a light-based method, they were able to switch dopamine-producing cells "on" or "off" during the task.

If rapid dopamine bursts were responsible for movement vigor, changing dopamine levels at that exact moment should have altered how fast or forcefully the mice moved. Instead, adjusting dopamine activity during movement made no difference.

When the researchers tested levodopa, they found that the drug improved movement by raising the brain's overall dopamine level. It did not work by restoring the short-lived dopamine bursts that occur during motion.

Toward More Targeted Parkinson's Treatments

More than 110,000 Canadians are currently living with Parkinson's disease, and that number is expected to more than double by 2050 as the population ages.

According to the researchers, a better understanding of why levodopa works could guide the development of future treatments that focus on maintaining steady dopamine levels rather than targeting rapid dopamine signals.

The findings also encourage researchers to reexamine older treatment strategies. Dopamine receptor agonists have shown benefits in the past but often caused side effects because they affected large areas of the brain. The new insight may help scientists design safer therapies that act more precisely.

About the Study

"Subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not specify the vigor of ongoing actions" by Haixin Liu and Nicolas Tritsch et al., was published in Nature Neuroscience.

The study was funded by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec.

Story Source:

Materials provided by McGill University. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Haixin Liu, Riccardo Melani, Marta Maltese, James Taniguchi, Akhila Sankaramanchi, Ruoheng Zeng, Jenna R. Martin, Nicolas X. Tritsch. Subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not specify the vigor of ongoing actions. Nature Neuroscience, 2025; 28 (12): 2432 DOI: 10.1038/s41593-025-02102-1

Cite This Page: