Simple light trick reveals hidden brain pathways in microscopic detail

A simple new imaging trick reveals microscopic fiber networks that have been hidden in tissue slides for decades.

- Date:

- December 9, 2025

- Source:

- Stanford Medicine

- Summary:

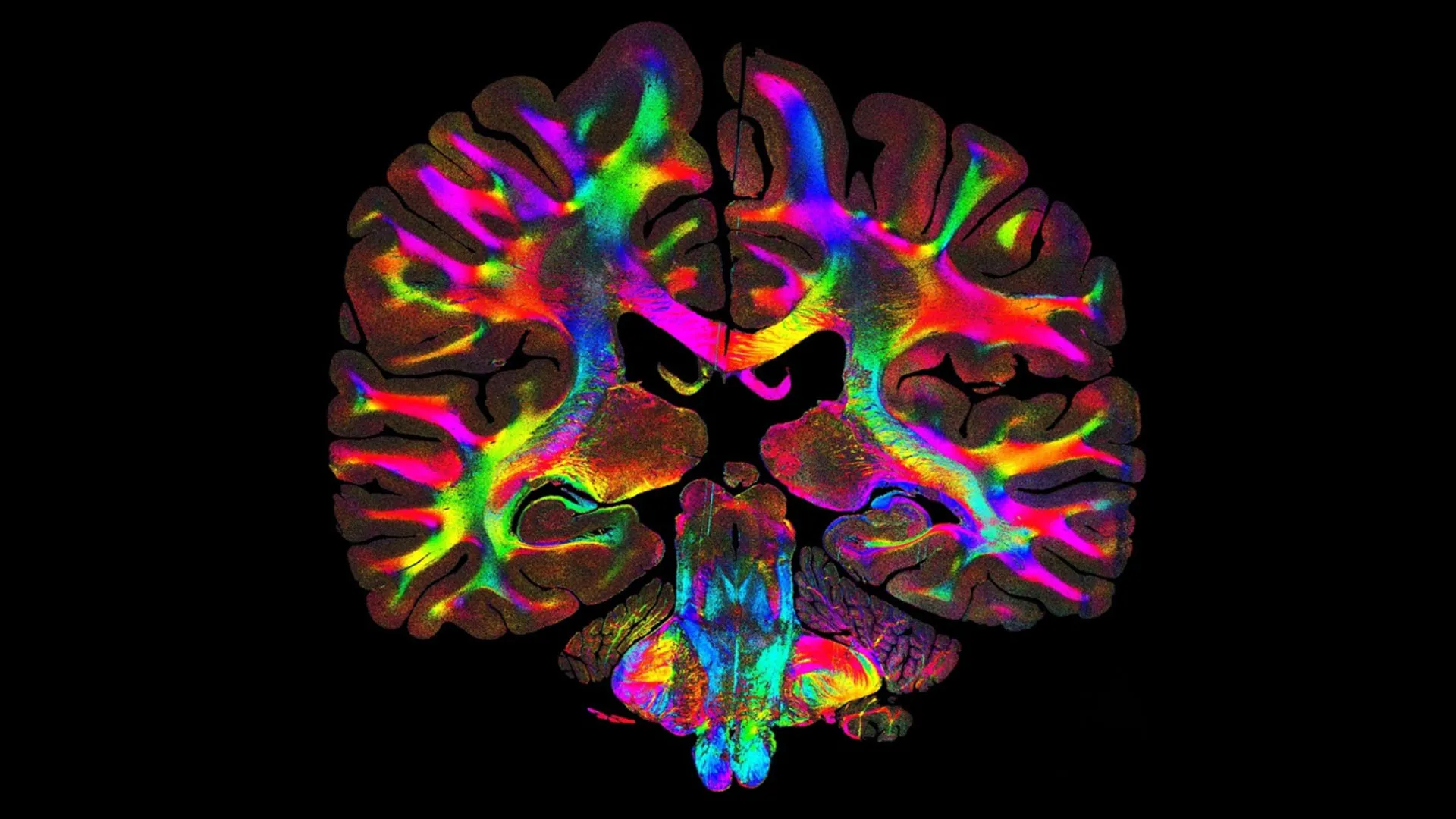

- Microscopic fibers secretly shape how every organ in the body works, yet they’ve been notoriously hard to study—until now. A new imaging technique called ComSLI reveals hidden fiber orientations in stunning detail using only a rotating LED light and simple microscopy equipment. It works on any tissue slide, from fresh samples to those more than a century old, allowing scientists to uncover microstructural changes in disorders like Alzheimer’s and even explore the architecture of muscle, bone, and blood vessels.

- Share:

Every tissue in the human body contains exceptionally small fibers that help coordinate how organs move, function and communicate. Muscle fibers guide physical force, intestinal fibers support the motion of the digestive tract, and brain fibers carry electrical signals that allow different regions to exchange information. Together, these intricate fiber systems help shape the structure of each organ and keep them operating properly.

Many diseases disrupt these delicate networks. In the brain, damage to fiber connections appears across nearly all neurological disorders, where it contributes to changes in neural communication.

Although these microscopic structures play essential roles, they have long been challenging to study. Researchers have struggled to determine how fibers are oriented inside tissues, which has made it difficult to fully understand how they change in health and disease.

A Simple Method for Revealing Hidden Microstructure

A research team led by Marios Georgiadis, PhD, instructor of neuroimaging, has now introduced an approach that makes these hard-to-see fiber patterns visible with exceptional clarity and at a relatively low cost.

Their technique, described in Nature Communications, is known as computational scattered light imaging (ComSLI). It can reveal the orientation and organization of tissue fibers at micrometer resolution on virtually any histology slide, regardless of how it was stained or preserved -- even if the slide is many decades old.

Michael Zeineh, MD, PhD, professor of radiology, served as co-senior author with Miriam Menzel, PhD, a former visiting scholar in Zeineh's laboratory.

"The information about tissue structures has always been there, hidden in plain sight," Georgiadis said. "ComSLI simply gives us a way to see that information and map it out."

How ComSLI Maps Fiber Orientation

Traditional imaging strategies come with significant limitations. MRI can highlight large anatomical networks but cannot capture tiny cellular structures. Histology techniques often require specialized stains, high-end equipment and carefully preserved samples, and they still struggle to depict fiber crossings clearly.

ComSLI relies on a basic physical principle: when light encounters microscopic structures, it scatters in different directions based on their orientation. By rotating the light source and recording how the scattering signal changes, researchers can reconstruct the direction of the fibers within each pixel of an image.

The method requires only a rotating LED light and a microscope camera, making the setup accessible compared with other forms of advanced microscopy. After the images are collected, software analyzes delicate patterns in the scattered light to generate color-coded maps of fiber orientation and density, known as microstructure-informed fiber orientation distributions.

ComSLI is not limited by sample preparation. It works with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (a standard in hospitals and pathology labs) as well as fresh-frozen, stained or unstained slides.

Scientists can also revisit slides originally created for unrelated projects, even those stored for decades, allowing new structural insights without altering the samples.

"This is a tool that any lab can use," Zeineh said. "You don't need specialized preparation or expensive equipment. What excites me most is that this approach opens the door for anyone, from small research labs to pathology labs, to uncover new insights from slides they already have."

Mapping Neural Microstructure and Disease

A major goal in neuroscience has been to chart the brain's microscopic pathways with high precision. Using ComSLI, Georgiadis and colleagues visualized full formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human brain sections and standard-sized slides, revealing detailed fiber structures throughout the tissue.

They also examined how these fibers change in neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, leukoencephalopathy and Alzheimer's disease.

One focus was the hippocampus, a deep-brain region central to memory formation and retrieval and often affected early in neurodegeneration. When comparing a hippocampal section from a patient with Alzheimer's disease to a healthy sample, the team observed clear structural deterioration. Fiber crossings that normally help connect regions of the hippocampus were greatly diminished, and a major pathway responsible for bringing memory-related signals into the region (the perforant pathway) was barely visible. The healthy hippocampus, in contrast, showed a dense and interconnected network of fibers across the entire area. With these detailed maps, researchers can see how memory circuits break down as disease progresses.

To test the limits of the method, the researchers analyzed a brain section prepared in 1904. Even in this century-old sample, ComSLI identified intricate fiber patterns, allowing scientists to study historical specimens and explore how structural features evolve across generations of disease.

Applications Beyond the Brain

Although first designed for brain research, ComSLI also works well in other tissues. The team used it to study muscle, bone and vascular samples, each revealing unique fiber arrangements tied to their biological functions.

In tongue muscle, the method highlighted layered fiber orientations linked to movement and flexibility. In bone, it captured collagen fibers that align with mechanical stress. In arteries, it showed alternating collagen and elastin layers that support both strength and elasticity.

This ability to map fiber orientation across species, organs and archival specimens could significantly change how scientists investigate structure and function. It also means that millions of stored slides around the world may contain untapped microstructural information.

"Although we just presented the method, there are already multiple requests for scanning samples and replicating the ComSLI setup -- so many labs and clinics would like to have micron-resolution fiber orientation and micro-connectivity on their histology sections," Georgiadis said. "Another exciting plan is to go back to well-characterized brain archives or brain sections of famous people, and recover this micro-connectivity information, revealing 'secrets' that have been considered long lost. This is the beauty of ComSLI."

Story Source:

Materials provided by Stanford Medicine. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Marios Georgiadis, Franca auf der Heiden, Hamed Abbasi, Loes Ettema, Jeffrey Nirschl, Hossein Moein Taghavi, Moe Wakatsuki, Andy Liu, William Hai Dang Ho, Mackenzie Carlson, Michail Doukas, Sjors A. Koppes, Stijn Keereweer, Raymond A. Sobel, Kawin Setsompop, Congyu Liao, Katrin Amunts, Markus Axer, Michael Zeineh, Miriam Menzel. Micron-resolution fiber mapping in histology independent of sample preparation. Nature Communications, 2025; 16 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64896-9

Cite This Page: