Distant entangled atoms acting as one sensor deliver stunning precision

- Date:

- January 26, 2026

- Source:

- University of Basel

- Summary:

- Researchers have demonstrated that quantum entanglement can link atoms across space to improve measurement accuracy. By splitting an entangled group of atoms into separate clouds, they were able to measure electromagnetic fields more precisely than before. The technique takes advantage of quantum connections acting at a distance. It could enhance tools such as atomic clocks and gravity sensors.

- Share:

Researchers at the University of Basel and the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel have shown that quantum entanglement can be used to measure several physical quantities at the same time with greater accuracy than traditional methods allow.

Entanglement is often described as one of the most mysterious effects in quantum physics. When two quantum objects are entangled, measurements performed on them can remain strongly linked even when the objects are far apart. These unexpected statistical connections have no explanation in classical physics. The effect can appear as though measuring one object somehow influences the other at a distance. This phenomenon, known as the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox, was confirmed experimentally and recognized with the 2022 Nobel Prize in physics.

Using Distant Entanglement for Precision Measurements

Building on this foundation, a team led by Prof. Dr. Philipp Treutlein at the University of Basel and Prof. Dr. Alice Sinatra at the Laboratoire Kastler Brossel (LKB) in Paris demonstrated that entanglement between quantum objects separated in space can serve a practical purpose. Their work shows that spatially separated but entangled systems can be used to measure multiple physical parameters at once with improved precision. The results of the study were recently published in the journal Science.

"Quantum metrology, which exploits quantum effects to improve measurements of physical quantities, is by now an established field of research," says Treutlein. Around fifteen years ago, he and his collaborators were among the first to entangle the spins of extremely cold atoms. These spins, which can be imagined as tiny compass needles, could then be measured more precisely than if each atom behaved independently without entanglement.

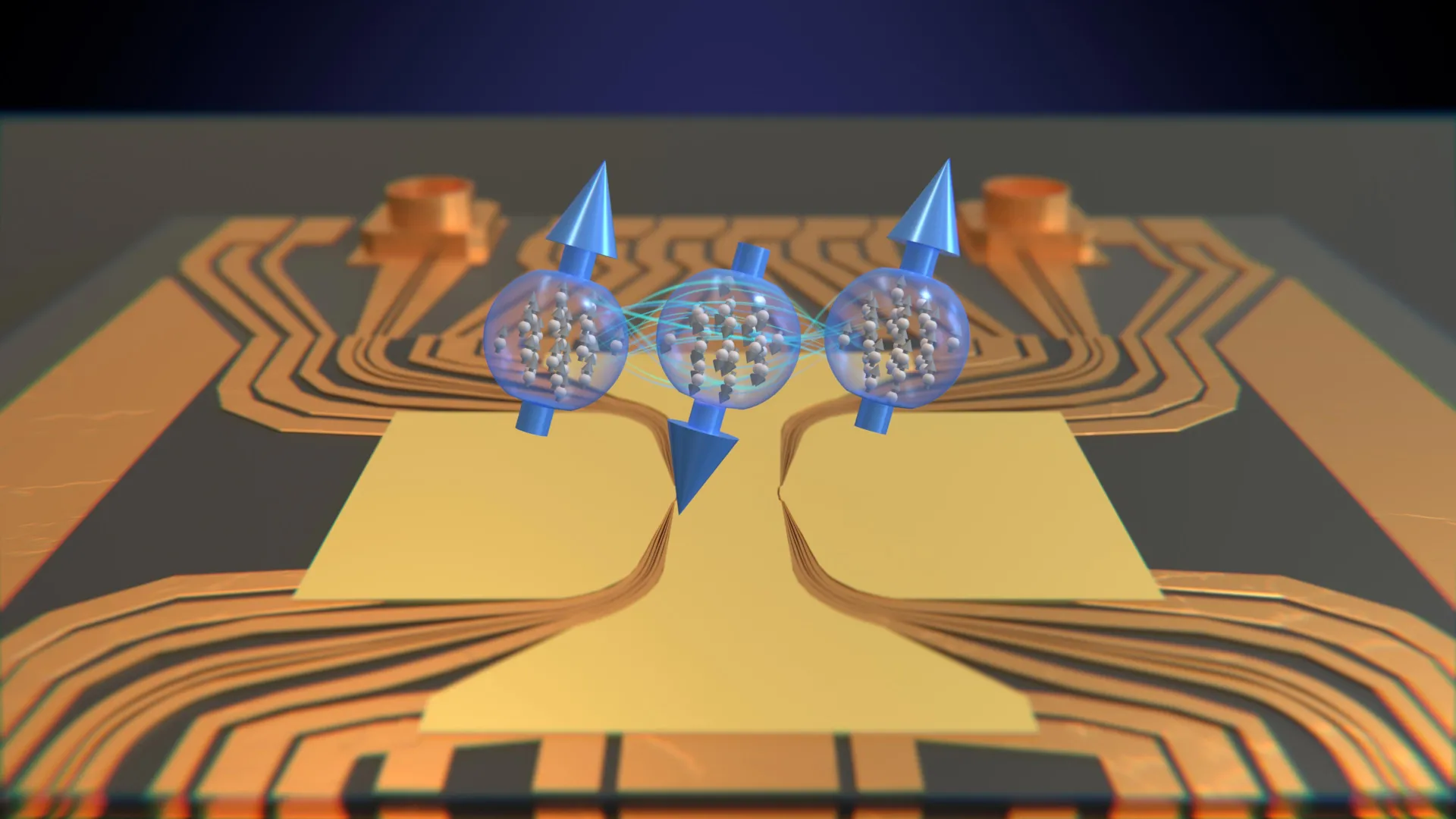

"However, those atoms were all in the same location," Treutlein explains: "We have now extended this concept by distributing the atoms into up to three spatially separated clouds. As a result, the effects of entanglement act at a distance, just as in the EPR paradox."

Mapping Fields With Entangled Atomic Clouds

This approach is especially useful for studying quantities that vary across space. For example, researchers interested in measuring how an electromagnetic field changes from place to place can use entangled atomic spins that are physically separated. As with measurements made at a single location, entanglement reduces uncertainty that arises from quantum effects. It can also cancel out disturbances that affect all of the atoms in the same way.

"So far, no one has performed such a quantum measurement with spatially separated entangled atomic clouds, and the theoretical framework for such measurements was also still unclear," says Yifan Li, who worked on the experiment as a postdoc in Treutlein's group. Together with colleagues at the LKB, the team studied how to minimize uncertainty when using entangled clouds to measure the spatial structure of an electromagnetic field.

To do this, the researchers first entangled the atomic spins within a single cloud. They then divided that cloud into three parts that remained entangled with one another. With only a small number of measurements, they were able to determine the field distribution with clearly higher precision than would be possible without entanglement across space.

Applications in Atomic Clocks and Gravimeters

"Our measurement protocols can be directly applied to existing precision instruments such as optical lattice clocks," says Lex Joosten, PhD student in the Basel group. In these clocks, atoms are held in place by laser beams arranged in a lattice and serve as extremely precise "clockworks." The new methods could reduce specific errors caused by how atoms are distributed within the lattice, leading to more accurate timekeeping.

The same strategy could also improve atom interferometers, which are used to measure the Earth's gravitational acceleration. In certain applications, known as gravimeters, scientists focus on how gravity changes across space. Using entangled atoms makes it possible to measure these variations with greater precision than before.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Basel. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Yifan Li, Lex Joosten, Youcef Baamara, Paolo Colciaghi, Alice Sinatra, Philipp Treutlein, Tilman Zibold. Multiparameter estimation with an array of entangled atomic sensors. Science, 2026; 391 (6783): 374 DOI: 10.1126/science.adt2442

Cite This Page: