What scientists found inside Titan was not what anyone expected

- Date:

- December 20, 2025

- Source:

- University of Washington

- Summary:

- For years, scientists thought Saturn’s moon Titan hid a global ocean beneath its frozen surface. A new look at Cassini data now suggests something very different: a thick, slushy interior with pockets of liquid water rather than an open sea. A subtle delay in how Titan deforms under Saturn’s gravity revealed this stickier structure. These slushy environments could still be promising places to search for life.

- Share:

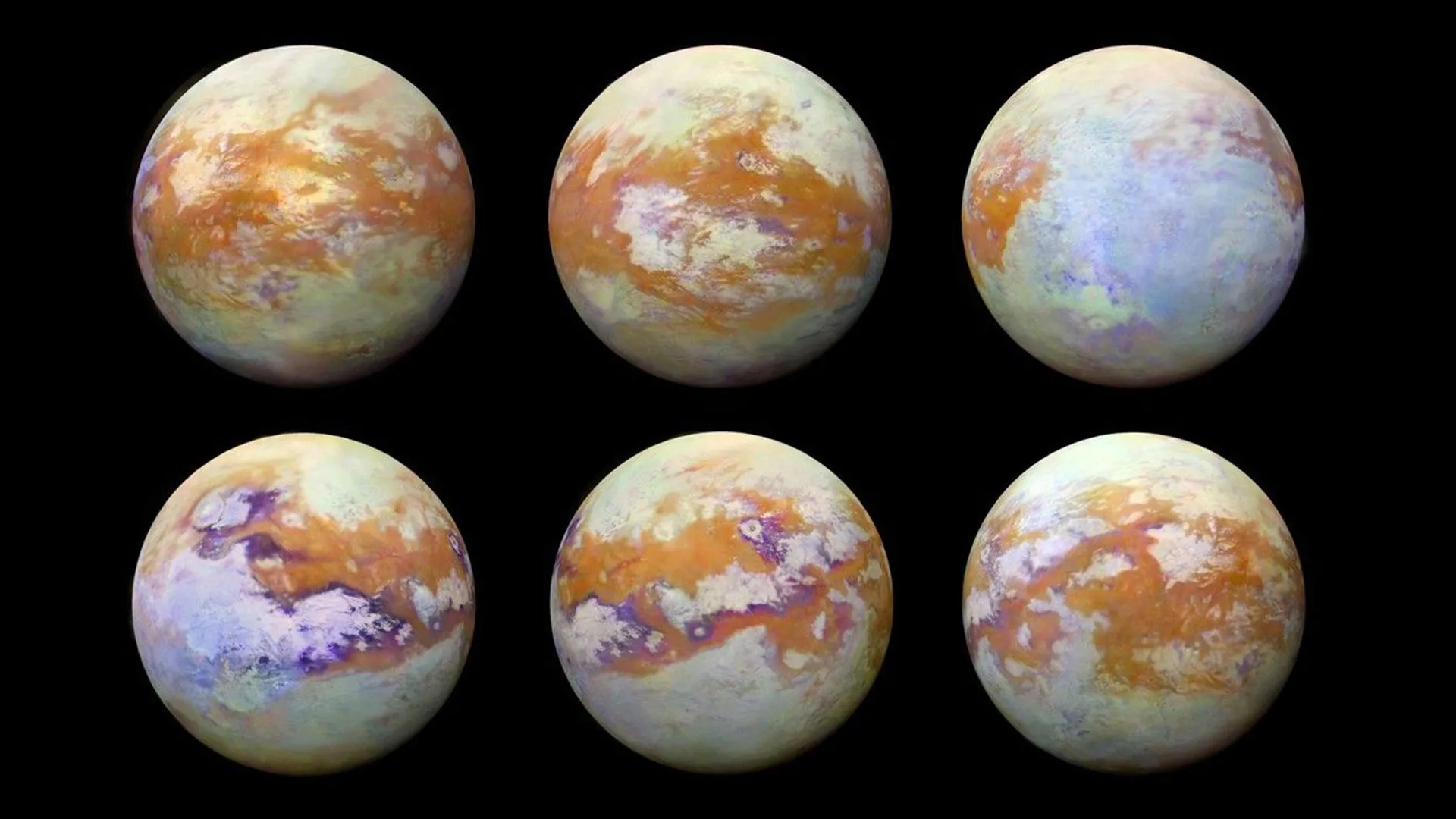

A new examination of spacecraft data collected more than ten years ago suggests that Saturn's largest moon, Titan, probably does not contain a massive ocean beneath its frozen surface, as scientists once believed. Instead, moving downward through Titan's icy shell would likely reveal additional layers of ice that gradually transition into slushy pathways and isolated pockets of liquid water closer to the moon's rocky interior.

Earlier interpretations of data from NASA's Cassini mission to Saturn led scientists to propose a deep ocean of liquid water hidden beneath Titan's ice. When researchers tested that idea using computer models, however, the results did not align with the physical characteristics seen in the data. A closer reanalysis produced new -- slushier -- conclusions. These results may prompt scientists to revisit assumptions about other icy worlds and refine how they search for life on Titan.

"Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we're probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers, which has implications for what type of life we might find, but also the availability of nutrients, energy and so on," said Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor of Earth and space sciences.

The study, published Dec. 17 in Nature, was led by NASA, with contributions from Journaux and Ula Jones, a UW graduate student of Earth and space sciences in his lab.

Cassini's Legacy and Titan's Unusual Surface

The Cassini mission began in 1997 and continued for nearly two decades, gathering extensive information about Saturn and its 274 moons. Titan -- shrouded by a hazy atmosphere -- stands out as the only place besides Earth where liquid is known to exist on the surface. With temperatures near -297 degrees Fahrenheit, that liquid is methane, not water. Methane forms lakes on Titan and even falls from the sky as rain.

As Titan travels around Saturn in an elongated orbit, scientists noticed that the moon stretches and compresses depending on its position relative to the planet. In 2008, researchers argued that this pronounced flexing could only occur if a large ocean existed beneath Titan's crust.

"The degree of deformation depends on Titan's interior structure. A deep ocean would permit the crust to flex more under Saturn's gravitational pull, but if Titan were entirely frozen, it wouldn't deform as much," Journaux said. "The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean, but now we know that isn't the full story."

A Subtle Time Lag Reveals a Slushy Interior

The new research adds an important factor that earlier studies did not fully consider: timing. Titan's changes in shape lag roughly 15 hours behind the strongest pull from Saturn's gravity. Moving a thick, sticky material requires more energy than shifting a free flowing liquid, similar to how stirring honey takes more effort than stirring water. By measuring this delay, scientists could estimate how much energy Titan absorbs as it deforms, offering insight into how thick or viscous its interior must be.

The amount of energy lost, or dissipated, inside Titan turned out to be far greater than expected if a global liquid ocean were present.

"Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan's interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses," said Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and lead author of the study.

Based on these findings, the researchers propose an interior made up largely of slush, with significantly less liquid water than previously assumed. This slushy material is thick enough to explain the delayed response to Saturn's gravity, while still containing enough water to allow Titan to change shape.

Radio Signals and Extreme Physics Support the Model

Petricca reached these conclusions by analyzing the frequencies of radio waves transmitted from the Cassini spacecraft during close fly-bys of Titan. Journaux helped interpret the results using thermodynamics. His work focuses on how water and minerals behave under intense pressure, knowledge that is critical for understanding whether other planetary environments might support life.

"The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes. Water and ice behave in a different way than sea water here on Earth," Journaux said.

At his planetary cryo-mineral physics laboratory at UW, researchers have spent years developing methods to recreate the extreme conditions found on other worlds. Using this work, Journaux provided Petricca and his colleagues with data describing how water and ice are expected to behave deep inside Titan.

"We could help them determine what gravitational signal they should expect to see based on the experiments made here at UW," Journaux said. "It was very rewarding."

What Slush Could Mean for Life on Titan

"The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan also has exciting implications for the search for life beyond our solar system," Jones said. "It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable."

While the idea of a vast ocean once fueled optimism about life on Titan, the researchers suggest the updated picture may actually improve the odds. Their analysis indicates that Titan's freshwater pockets could reach temperatures as high as 68 degrees Fahrenheit. In these smaller volumes of water, nutrients would be more concentrated than in a large ocean, potentially making it easier for simple life forms to survive.

Although scientists do not expect to find fish swimming through Titan's slushy channels, any life discovered there might resemble organisms found in Earth's polar regions.

Journaux is also part of NASA's upcoming Dragonfly mission to Titan, which is scheduled to launch in 2028. The findings from this study will help inform that mission, and Journaux hopes future data will provide both evidence of life and a definitive answer about the presence of an ocean beneath Titan's ice.

Co-authors include Steven D. Vance, Marzia Parisi, Dustin Buccino, Gael Cascioli, Julie Castillo-Rogez, Mark Panning and Jonathan I. Lunine from NASA; Brynna G. Downey at Southwest Research Institute; Francis Nimmo and Gabriel Tobie from the University of Nantes; Andrea Magnanini from the University of Bologna; Amirhossein Bagheri from the California Institute of Technology and Antonio Genova from Sapienza University of Rome.

This research was funded by NASA, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Italian Space Agency.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Washington. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Flavio Petricca, Steven D. Vance, Marzia Parisi, Dustin Buccino, Gael Cascioli, Julie Castillo-Rogez, Brynna G. Downey, Francis Nimmo, Gabriel Tobie, Baptiste Journaux, Andrea Magnanini, Ula Jones, Mark Panning, Amirhossein Bagheri, Antonio Genova, Jonathan I. Lunine. Titan’s strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean. Nature, 2025; 648 (8094): 556 DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09818-x

Cite This Page: