Scientists just found real teeth growing on a fish’s head

- Date:

- October 16, 2025

- Source:

- University of Washington

- Summary:

- Scientists discovered true teeth growing on the head of the spotted ratfish, a distant shark relative. The toothed structure, called a tenaculum, helps males hold onto females during mating. Genetic evidence shows these head teeth share the same origins as oral teeth, overturning assumptions that teeth only evolve in jaws. This discovery reshapes the story of dental evolution across vertebrates.

- Share:

When it comes to teeth, most vertebrates share the same basic blueprint. Regardless of their size, shape, or sharpness, teeth typically have the same genetic roots, similar physical makeup, and, almost always, a place in the jaw.

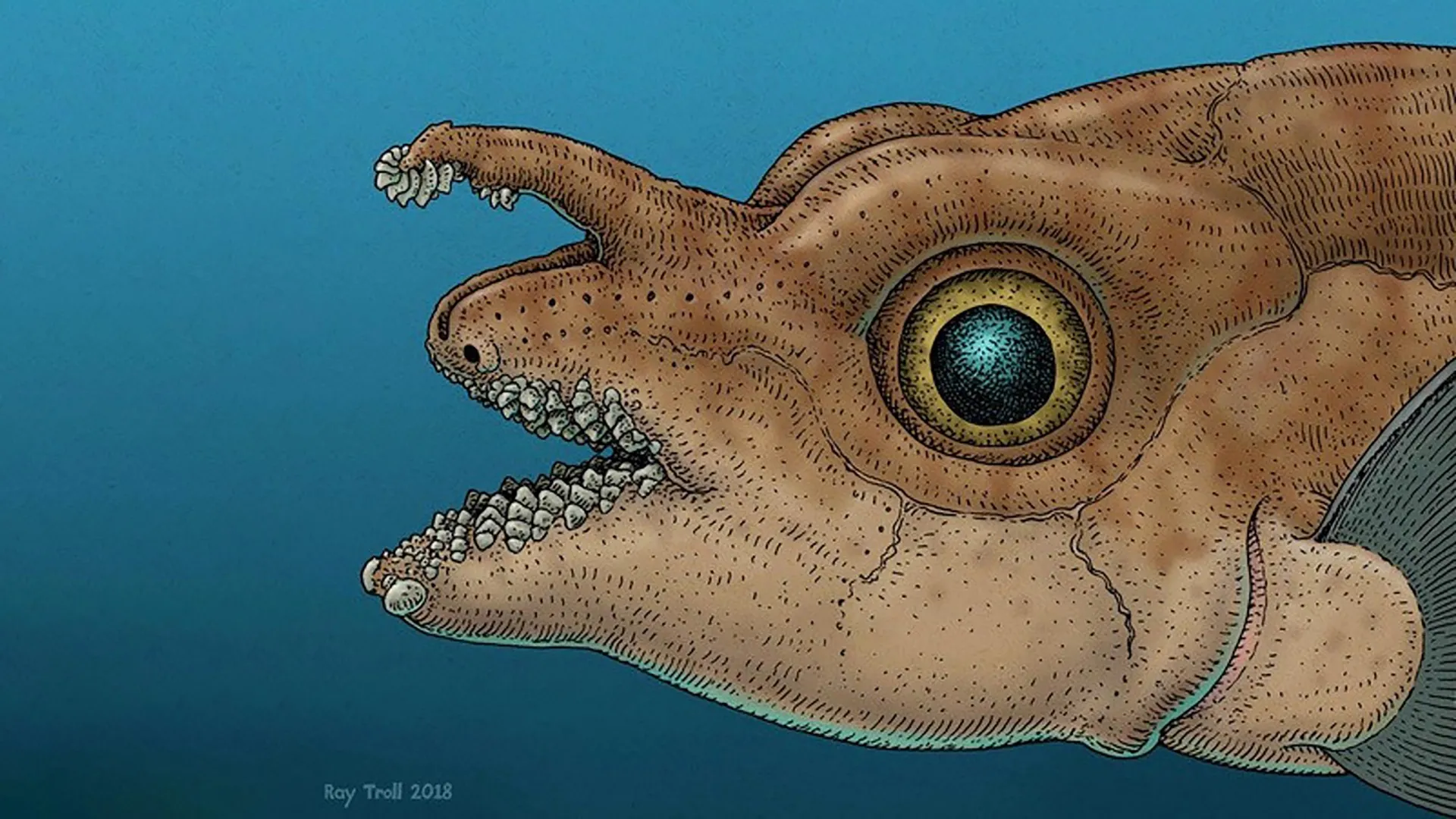

That assumption, however, may no longer hold true. Scientists studying the spotted ratfish, a shark-like species found in the northeastern Pacific Ocean, discovered that it has rows of teeth growing on top of its head. These teeth line a cartilage-based structure known as the tenaculum, a forehead appendage that loosely resembles Squidward's nose.

For years, biologists have debated where teeth originally came from -- an important question, given how vital they are to feeding and survival. Most discussions have focused solely on oral teeth, without exploring whether teeth might have evolved elsewhere on the body. The discovery of teeth on the tenaculum has reopened that debate, prompting researchers to ask how widespread such features might be and what they reveal about the history of vertebrate dentition.

"This insane, absolutely spectacular feature flips the long-standing assumption in evolutionary biology that teeth are strictly oral structures," said Karly Cohen, a UW postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Labs. "The tenaculum is a developmental relic, not a bizarre one-off, and the first clear example of a toothed structure outside the jaw."

The research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Spotted ratfish are among the most common fish in Puget Sound. They belong to a group of cartilaginous fish known as chimaeras, which diverged from sharks millions of years ago. Growing to about 2 feet in length, these fish are named for their long, slender tails that make up roughly half their body size. Only adult males develop a tenaculum on their forehead. When resting, it appears as a small white nub between their eyes, but when raised, it becomes a hooked, barbed organ covered in teeth.

Males use the tenaculum both for display and function. They raise it to ward off rivals and, during mating, use it to grip females by the pectoral fin, keeping the pair together in the water.

"Sharks don't have arms, but they need to mate underwater," Cohen said. "So, a lot of them have developed grasping structures to connect themselves to a mate during reproduction."

Spotted ratfish also use pelvic claspers for mating, similar to many other cartilaginous fish.

In most sharks, rays, and skates, the body is covered in small, tooth-like scales called denticles. But apart from the denticles on their pelvic claspers, spotted ratfish are largely smooth-skinned. This unusual lack of denticles led scientists to question what became of them -- and whether the teeth on the tenaculum might represent their evolutionary remnants.

Before conducting the study, researchers had two possibilities in mind. One was that the "teeth" were simply modified denticles, a leftover feature from ancient ancestors. The other suggested they were genuine teeth, similar to those found inside the mouth.

"Ratfish have really weird faces," Cohen said. "When they are small, they kind of look like an elephant squished into a little yolk sack."

The cells that form the oral region are spread farther afield, making it plausible that at some point, a clump of tooth-forming cells might have migrated onto the head and stuck.

To test these theories, the researchers caught and analyzed hundreds of fish, using micro-CT scans and tissue samples to document tenaculum development. While sharks can be quite hard to study, spotted ratfish abound in Puget Sound. They frequent the shallows surrounding Friday Harbor Labs, the UW research facility located on San Juan Island. They also compared the modern ratfish to ancestral fossils.

The scans showed that both male and female ratfish begin making a tenaculum early on. In males, it grows from a small cluster of cells into a little white pimple that elongates between the eyes. It attaches to muscles controlling the jaw and finally, erupts through the surface of the skin and sprouts teeth. In females it never materializes -- or mineralizes -- but evidence of an early structure remains.

The new teeth are rooted in a band of tissue called the dental lamina that is present in the jaw but has never been documented elsewhere. "When we saw the dental lamina for the first time, our eyes popped," Cohen said. "It was so exciting to see this crucial structure outside the jaw."

In humans, the dental lamina disintegrates after we grow our adult teeth, but many vertebrates retain the ability to replace their teeth. Sharks, for example, have "a constant conveyor belt" of new teeth, Cohen said. Dermal denticles, including the ones on the spotted ratfish's pelvic claspers, do not have a dental lamina. Identifying this structure was compelling evidence that the teeth on the tenaculum really are teeth and not leftover denticles. Genetic evidence also backed this conclusion.

"Vertebrate teeth are extremely well united by a genetic toolbox," Cohen said.

Tissue samples revealed that the genes associated with teeth across vertebrates were expressed in the tenaculum, but not the denticles. In the fossil record, they also observed evidence of teeth on the tenaculum of related species.

"We have a combination of experimental data with paleontological evidence to show how these fishes coopted a preexisting program for manufacturing teeth to make a new device that is essential for reproduction," said Michael Coates, a professor and the chair of organismal biology and anatomy at the University of Chicago and a co-author of the paper.

The modern adult male spotted ratfish can grow seven or eight rows of hooked teeth on its tenaculum. These teeth retract and flex more than the average canine, enabling the fish to latch onto a mate while swimming. The size of the tenaculum also appears to be unrelated to the length of the fish. Its development aligns instead with the pelvic claspers, suggesting that the migrant tissue is now regulated by other networks.

"If these strange chimaeras are sticking teeth on the front of their head, it makes you think about the dynamism of tooth development more generally," said Gareth Fraser, a professor of biology at the University of Florida and the study's senior author.

Sharks often serve as the model for studying teeth and development because they have so many oral teeth and are covered in denticles. But, Cohen added, sharks possess just a sliver of the dental diversity captured by history. "Chimeras offer a rare glimpse into the past," she said "I think the more we look at spiky structures on vertebrates, the more teeth we are going to find outside the jaw."

This research was funded by National Science Foundation, the Save Our Seas Foundation, and internal endowments at Friday Harbor Labs supporting innovative early-career research.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Washington. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

- Karly E. Cohen, Michael I. Coates, Gareth J. Fraser. Teeth outside the jaw: Evolution and development of the toothed head clasper in chimaeras. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2025; 122 (37) DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2508054122

Cite This Page: